Anne Laure Sacriste

RIVER OF SHADOWS

25 January – 8 March 2025

Atrata by Gil Presti

30 galerie de Montpensier

Jardin du Palais Royal

75001 Paris

Anne Laure Sacriste, born in 1970, is a French artist who lives and works in Paris. Her practice encompasses a variety of mediums, including painting, engraving, drawing, film and installation, often incorporating historical references and engaging with a broader art historical context.

Her work has been featured in numerous solo and group exhibitions, including Dialogue inattendu Morisot Sacriste, Portrait de B. M. étendue, Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris, 2023; Le Monde sans les mots, European Centre for Contemporary Artistic Actions, Strasbourg, 2023; Toguna, Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 2018; Vingt-quatre heures de la vie d’une femme, Musée d’Art Moderne et contemporain de Saint-Etienne, 2018.

Public collections : National Foundation for Contemporary Art (FNAC) in Paris; Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Saint-Etienne; Regional Foundations for Contemporary Art (FRAC) in Normandy, Auvergne, Alsace.

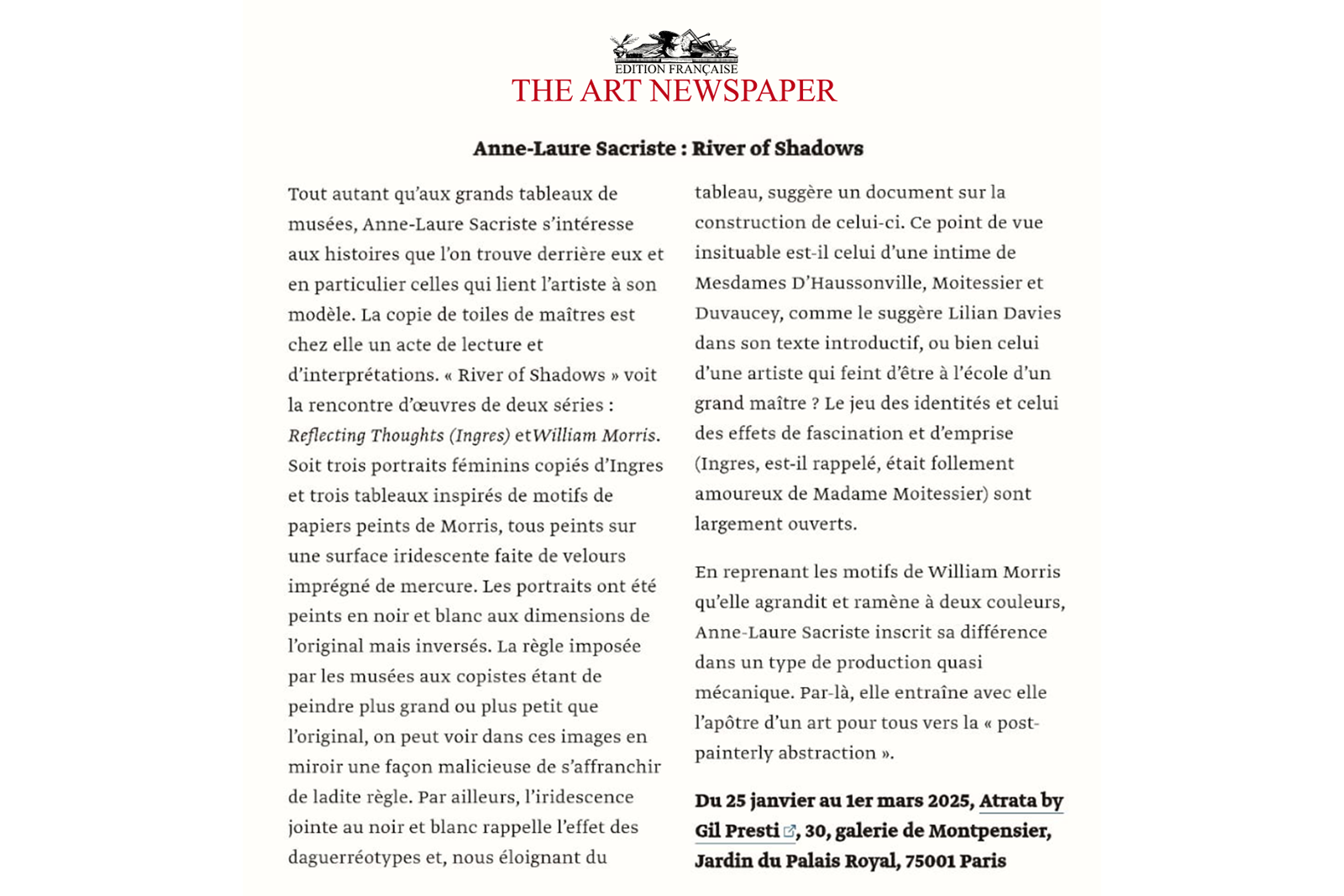

Appropriating her exhibition title from Rebecca Solnit’s book on Eadweard Muybridge and the “technological Wild West,” in “River of Shadows,” French artist Anne Laure Sacriste presents works from two painting series: Reflecting Thoughts (Ingres) and William Morris.

As a student at Parsons in the late 80s, Sacriste immersed herself in the work of Jim Jarmusch, fascinated by his long traveling shots, as well as David Lynch, inspired by the cinematographer’s construction of enigma in a collage of images. Sacriste doesn’t hesitate when I ask her favorite Lynch: Lost Highway (1997). Patricia Arquette’s double role, as resented wife and seductress, echoes the uncanny process of film itself, a phantasmagoric repetition of the real that Sacriste toys with in paint.

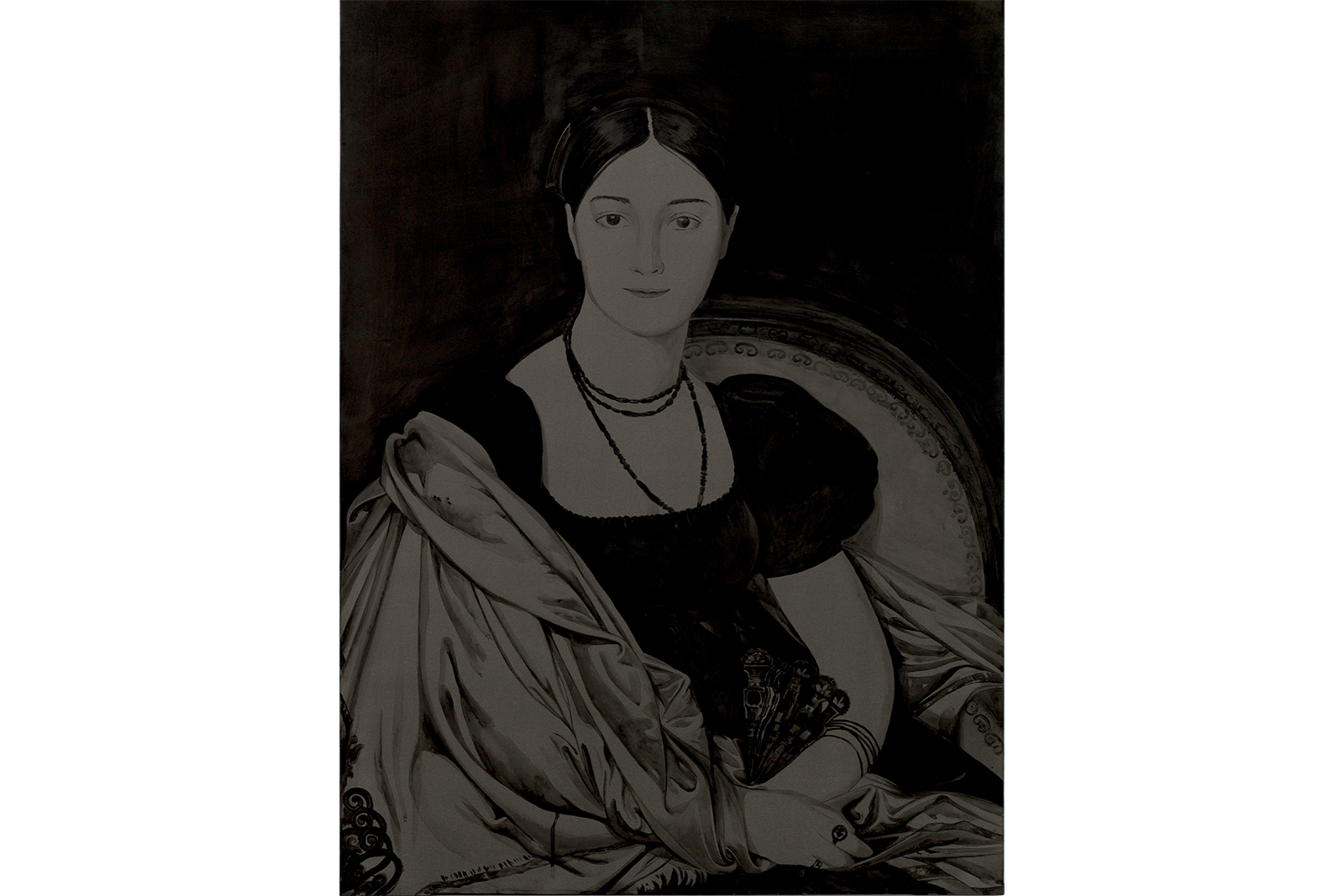

The ambiguous, reflective surfaces of Sacriste’s portraits echo Louis Daguerre’s mercury smoke process and copper-plated silver. The daguerreotype’s bewitching surface, that once shared the same space as its captured subjects, Sacriste summons here. Thanks to the discovery of gravure at Beaux Arts in the early 90s, Sacriste still revels in the medium’s reliance on what she calls “blind drawing.” The artist’s marks in dry point only appear through a subsequent chemical process. Traces, like shadows, are proof of the real, the artist’s hand, her memory. Similar to Andy Warhol’s Shadows series (1978-1979), an inspiration for Sacriste when she saw his eponymous exhibition at the Musée d’art Moderne in Paris (curated by Sébastien Gokalp, 2015), her work reveals cracks in the obsessive practice of repetition. For both artists, the mechanical process provides a space in which memories and ghosts can emerge.

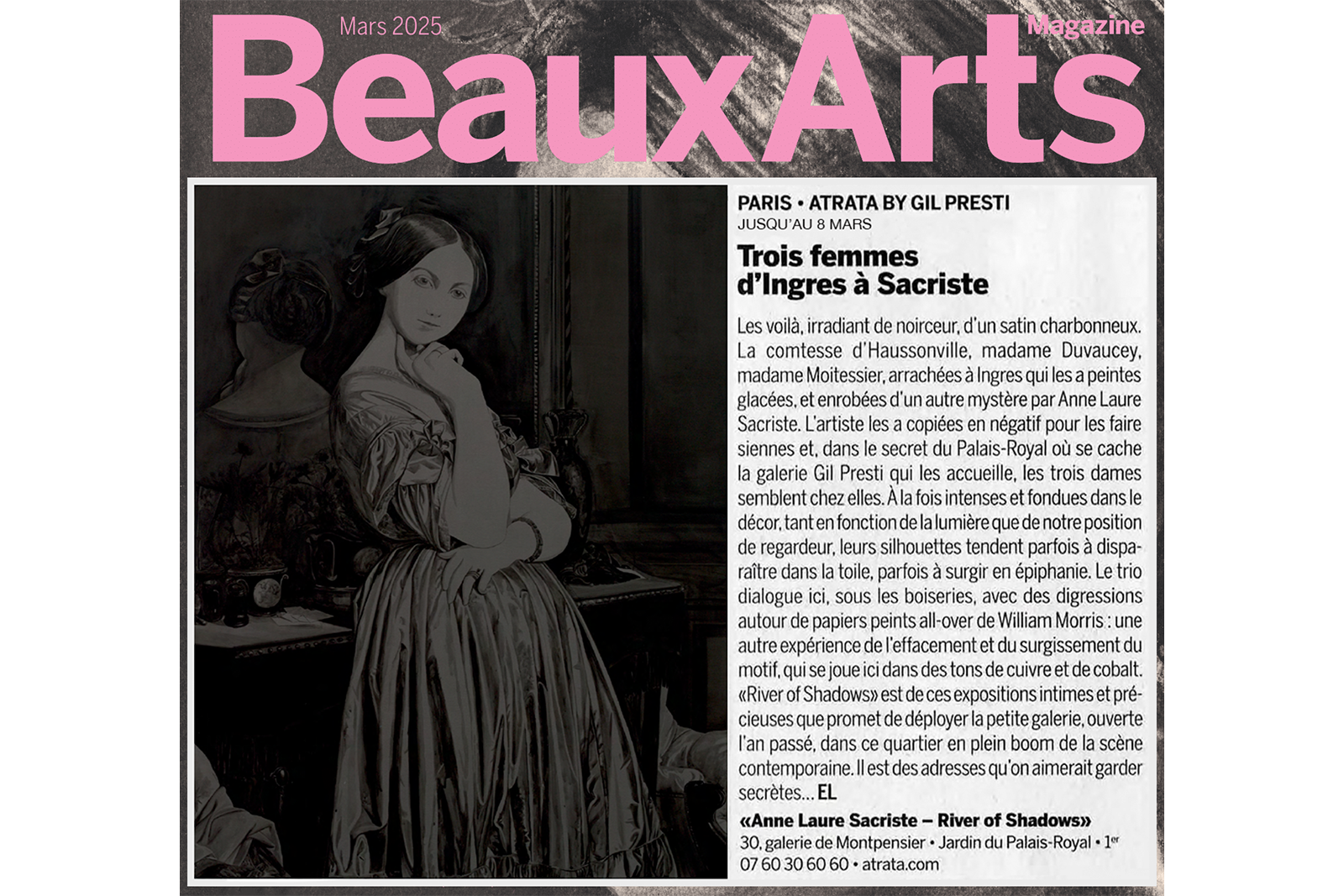

Ingres, a contemporary of Daguerre’s, entered Sacriste’s visual lexicon in the form of a postcard of the 19th century master’s Portrait de madame de Senonnes (1814). This printed reproduction of the canvas, once rescued by a local artist from an antiques dealer and now a treasure of the Musée d’arts de Nantes, “followed” the young artist from one studio to the next. “My muse,” Sacriste says. Here, in a midnight palette on iridescent canvas, surfaces like liquid mercury dressed in velvet, Sacriste’s Mme Duvaucey (2019), Mme Moitessier (2020) and Comtesse d’Haussonville (2020) exact, or nearly, the dimensions of Ingres’s canvases. Though, as if viewed in a mottled mirror, Sacriste shades and reverses Ingres’s compositions. Under Sacriste’s delicate brush, the sky-blue satin gown of Louise, princess of Broglie, future Comtesse d’Haussonville, shines the color of moonbeams and leans to the left. In the painting her son, pressured with heavy inheritance taxes, sold to dealer Georges Wildentstein (who promptly found a buyer in the American industrialist Henry Frick), Louise’s soft back leans right. In Sacriste’s paintings and precise installations, a movement emanates, like a back-and-forth between absence and presence. She shows us the porosity between the living being and its specter. When she speaks of visiting Mesdames Duvaucey, Moitessier and the red-ribbon crowned Louise, today housed museums around the world, it’s almost as if she’s talking about a circle of friends.

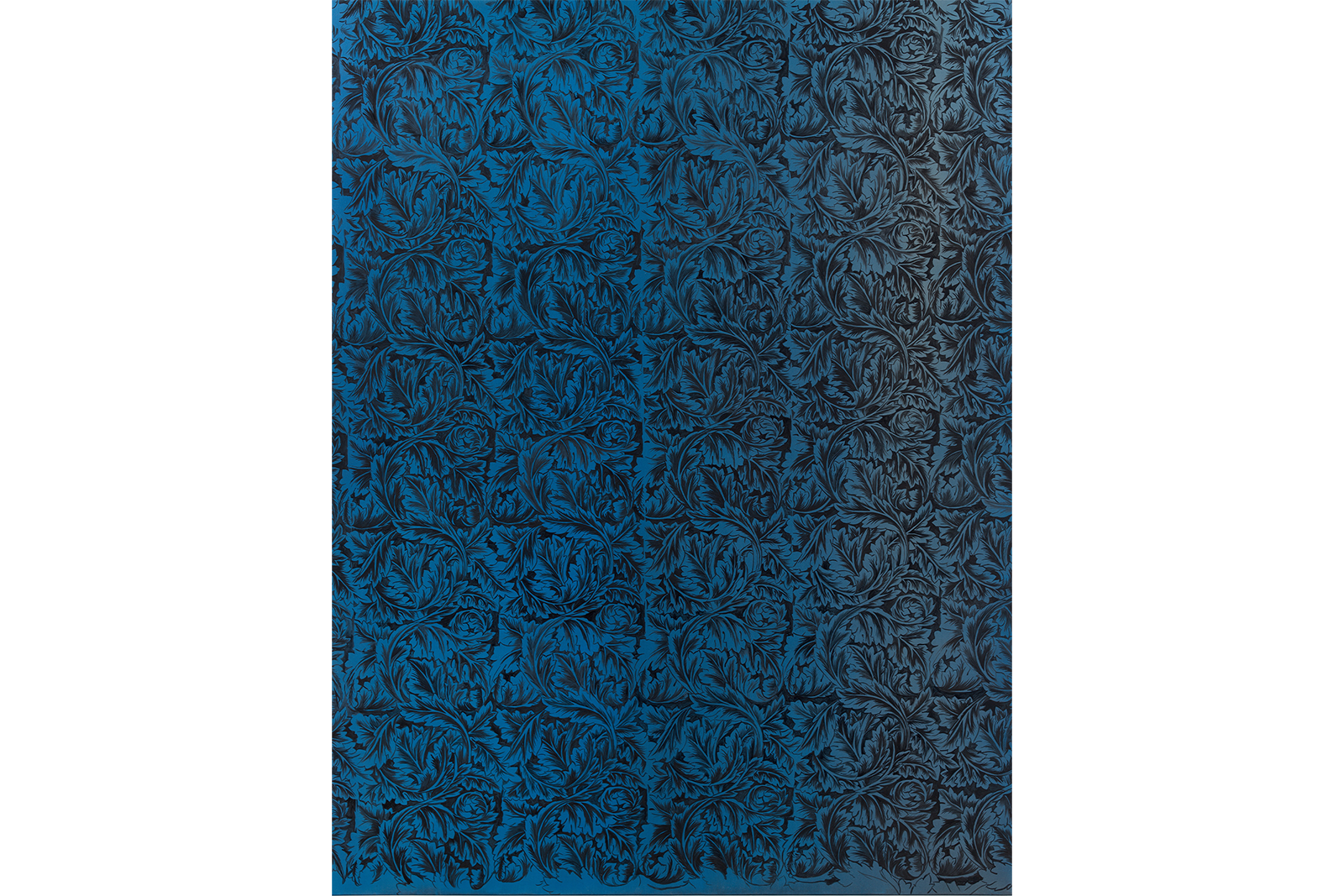

Here, these female portraits are in the company of Sacriste’s William Morris inspired canvases, Copper floral (2016), After Morris Blue (2018), and Moiré floral (2018). Reproducing the motifs of Morris’s wallpapers, Sacriste incorporates her canvases with the decorative and architectural. “Moiré,” a term derived from the glistening weave of mohair, describes a rippled, watery effect, apparent in silky textile or digital photos of a television screen. Here, together with Sacriste’s trembling female reflections, her William Morris series evokes the private space of le boudoir. From the French verb bouder (to sulk), the boudoir names both a secluded space of feminine retreat and as well as an historic site of uninhibited conversation. It was inside the bedrooms of wealthy women that some of the first women’s salons developed in 18th-century France.

This possibility for speech is essential, as Solnit emphasizes in the polemical book she published shortly after her impressive tome on Muybridge, Men Explain Things to Me. For Solnit, the silencing of women is on the same spectrum as violence against women. In this exhibition, Sacriste’s Madame Moitessier and the Vicomtesse D’Haussonville seem almost to whisper to one another, conspiratorially. It is said that Ingres was madly in love with Madame Moitessier, and she, refusing his advances, the male painter locks her in a canvas, symbolically soiling her dress inside the floral boudoir. Her arms, her neck, apparently boneless, in an anatomy invented by Ingres, resembles the shape and color of sugar-dusted biscuits: boudoirs. Gourmande and sexual pleasures are easily conjured under the arcades of Palais Royal, which the Duc d’Orléans erected in the late 18th century as a source of income. Off limits to municipal police, free exchange inside intimate échoppes, rented to the highest bidders, bubbled effervescent through the early 19th century. Here, the canvases in “River of Shadows” offer an immersive, disruptive experience of painting.

—– Lillian Davies